History

A Scot, a New Mexican, two African-Americans, three Africans, and a bunch of once-and-future European-Americans walk into a… [no, this is not a bar joke] … slave castle. Notwithstanding the specific and varied ethnic compositions of the many people traveling as part of our group, the labels above warrant some attention. The mixed blood of the colonized, the colonizers, and those who remained all found their way into this hallowed ground, together, some 200 years after the last slaves were thrust through the Door of No Return.

I wondered, as someone who represents none of the ethnicities involved in the slave trade, but who carries a skin color that affords me the privilege of the system that emerged out of these tragedies, how this experience was different for each of the individuals who shared my travels. Who among us carried some responsibility for these past events, and their present ramifications? All of us? Some of us? None of us?

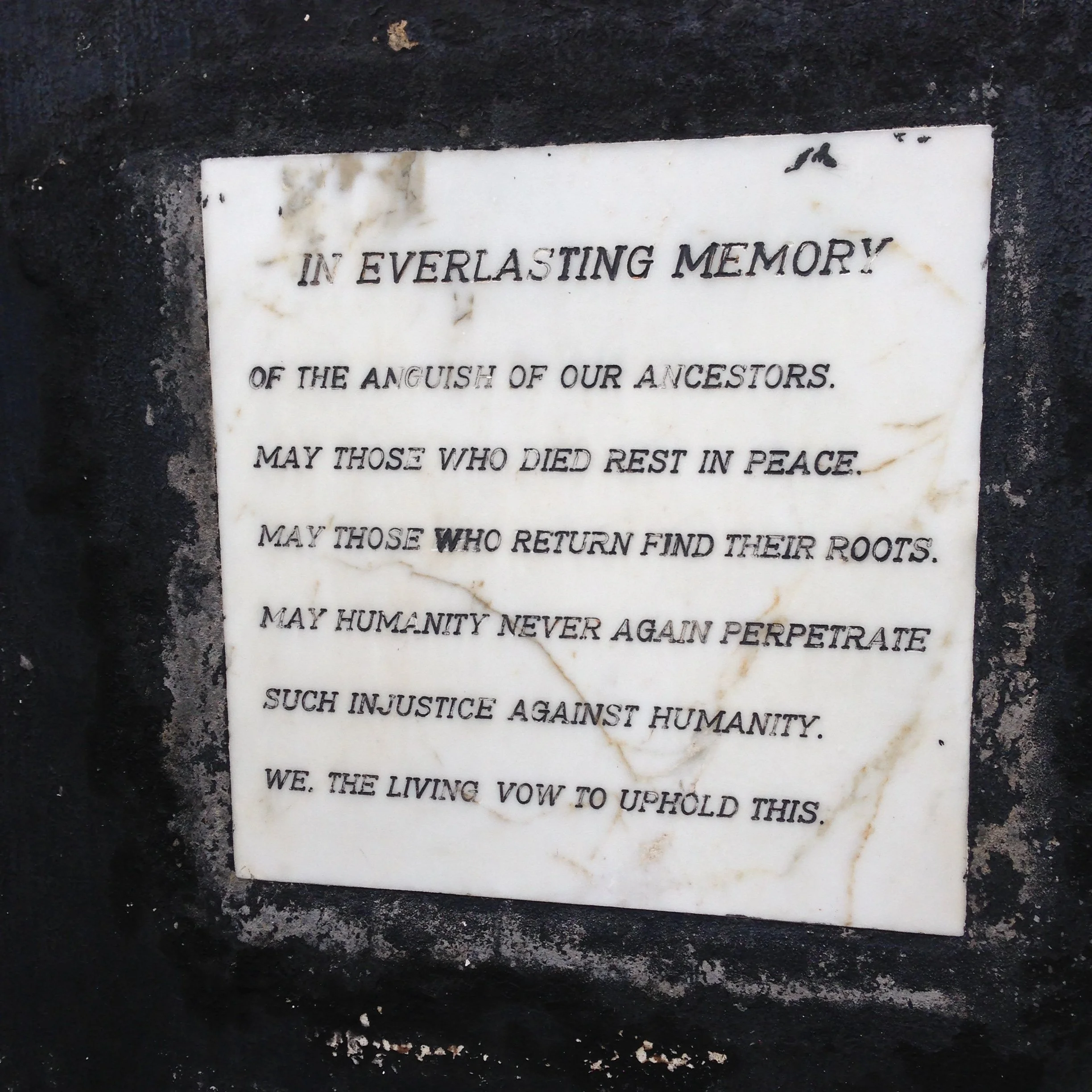

I’ve stood before in places that felt a bit like the slave castle: French execution sites, the bowels of the pyramids, cavernous cathedrals that hosted the lives and deaths of countless people who are separated from me at those moments only by time. The visceral scent of past history intrudes on the present, and the Elmina Castle was no exception. The Atlantic slave trade probably represents one of the most powerful blemishes on human history of all time, and it is captured in stone. The castle commemorates several hundred years of intolerable human cruelty with the banners of the dueling gods of the Portuguese and the Dutch hanging overhead. Plaques have been erected to make sure that we never forget what happened there.

I wonder, with internal conflicting opinions, whether it is a good idea to commemorate and visit these places. Does it help us to see it, to smell it, to learn about it? To walk in the footsteps of unimaginable suffering? I find myself unsettled by the sometimes trite and disconnected “never forget” sentiments promulgated by people who have limited personal connection to historical tragedies. I do believe that we have a responsibility to know our history. Yet sometimes it seems that never forgetting can contribute to the entrenchment of isolating ideas, to a myopic nationalism that is dangerous in an interconnected world, and to intergenerational prejudices that force us to look at individuals and to see the errors of their grandfathers, or even further-removed relations. Where is the line, the one that allows us to remember those who are still living who deserve all of the support the world can give them, the line between remembrance and forgetting that will help bring about the progress we dream about?